The frequency of clinical orientation presents a multitude of challenges to medical administrators and educators.

Between five rotations conducted annually for interns and residents, and another two or three for registrars, pressure to create tailored orientation experiences enabling a smooth transition into new roles is significant.

Although a great orientation experience is a pivotal step in bringing new clinicians into an organisation, the best intentions aren’t always reflected in the execution.

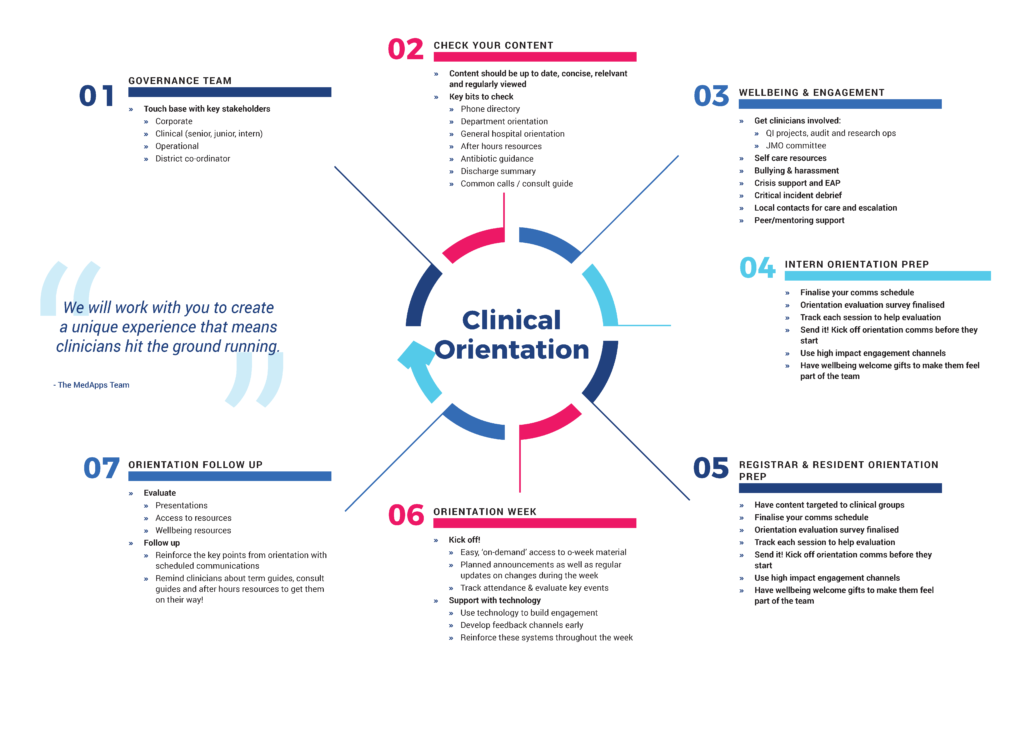

If clearer guidance about how to step through preparation of your hospital’s clinical orientation is what your delivery team needs, our on the ground experience, feedback, and expertise has led to the development of the the following proven steps to will help build confidence in your approach.

Step 1 – Engage the Governance Team

Stakeholder engagement is a major factor in the success of any clinical orientation (1).

In terms of preparation, be sure to cast your net widely enough to capture input from corporate and clinical, as well as from all levels of the organisation, from the junior medical team to those in senior roles. If relevant, engage at the network or district level too.

Review previous evaluation reports and ask each stakeholder to consider previous orientation experiences to identify what did and didn’t go well from their perspective. As part of this process, find out what takes time and frustrates them when staff are not onboarded or orientated properly. Direct input like this is invaluable and will help improve future orientation experiences and lead to better patient care.

Step 2 – Check your content

Vast amounts of content is communicated at orientation, however it’s not only junior clinicians who can feel overwhelmed. Identifying who needs to know what, by when, is a key challenge faced by medical administrators and educators. Knowing the content format that is easy for each audience to access and understand while ensuring it is all up to date can be just as challenging. Make it a goal that all relevant parties share an understanding of the content requirements, and aim for all content to be ready well in advance of the orientation start date. And a final recommendation: Adhere to the mantra that content should be current, concise, relevant, and reviewed.

In terms of communication, avoid sending a barrage of emails with embedded links or attachments if engagement is your priority. Instead, identify key information (for example, phone directories, after hours resources) and ‘drip feed’. Tailor information to specific facilities, departments or units, as required. This will also provide a more personalised feel to the experience.

Step 3 – Plan for clinician wellbeing and engagement

Adopt an approach that keeps clinician wellbeing and engagement front and centre of the clinical orientation experience.

It’s vital that hospitals communicate how clinicians can become involved in the organisation (2), including options for professional and social activities. Your communication needs to be more than a list of where to go when things are tough. Instead, aim to build a culture that fosters a cohesive, supportive team because prevention is the best medicine.

Make new clinicians aware of any quality improvement projects underway, as well as audit and research opportunities being delivered. Your JMO committee should be highly visible during orientation, allowing new starters to connect and identify the activities in which they can be involved during the current rotation.

Clinician burnout is well and truly problematic (3), so communicating what’s available, and making it easy to find is essential. The availability and scope of wellbeing resources that provide for self-care, address bullying and harassment, deliver crisis and peer/mentoring support should all be communicated clearly at every orientation.

Step 4 – Prep the Intern Orientation

The ideal clinical orientation is one that is tailored to the audience.

In practical terms, this translates to preparing content specific to interns, residents, and registrars – or any other training clinician – rather than relying on a single body of content that is applied universally. It also means making content available in advance of the orientation period, allowing the new interns to familiarise themselves and hit the ground running.

This may require that you adopt a different content format to what’s currently in place if your organisation still relies on posters, handing out 120 page manuals, or sending group emails, when the audience is highly tech savvy.

And if you’re keen to help this cohort feel part of the team, be sure to put together a simple welcome pack. A little goes a long way to creating a positive culture.

Step 5 – Prep the registrar and resident orientation

Although the process for preparing the registrar and resident orientation is the same as that used for interns, content must be targeted towards the experience or seniority of the clinician, and ideally, delivered using technology to build engagement.

In all other respects, however, adopt the same principles: communicate early, track and evaluate the orientation experience, and follow up to ensure new employees are settling in. Taking this approach increases the chance they will more quickly become an effective member of your hospital’s team.

Step 6 – Deliver your orientation week

Activities conducted during your orientation week will be a mix of practical sessions and presentations by various departments and units. Of course, many of these have follow up materials and resources, so communication must allow for easy access, ideally both offline and online. The usefulness of any resource is severely diminished if the people who need it either don’t know it exists or can’t find it.

Clear communication throughout orientation is essential too. Ensure you have the mechanisms by which the latest information can be communicated, allowing sufficient flexibility for updates and changes to be delivered in good time.

Step 7 – Follow up the orientation

Wrapping up the orientation experience is the ideal time to take stock of how things went. While the event is fresh in the mind’s of all involved, it is easier to review and refine the process, identifying what works, what generated the most and least interest, opportunities for improvement, and whether the right information could be accessed easily by the intended audience.

Continue the dialogue by following up with clinicians after orientation. Apart from allowing you to elicit feedback, it’s another contact point through which you can remind new team members about the resources that are available and how to access them.

A final word about clinical orientation

The work of clinical orientation is never done. Each time the doors of your hospital open to a new clinical team, there is an opportunity to refine and improve. Rather than see this as more work, consider it the pathway to delivering a great orientation experience that sets your people up to deliver the very best in healthcare.

Clinical orientation presents many challenges to the medical administrators and educators responsible for its delivery. Developing a strategy and following clear steps can yield long term benefits for any healthcare organisation and the people directly impacted by the process – the training clinicians. If you’d like to learn more about creating an orientation experience that simplifies access to clinical and hospital guidelines, clinician communication, and employee education and training, the dedicated team at Med Apps can help. Learn more at Med App, connect with us, or uncover the possibilities when you book a complimentary demonstration.

- Mulroy, Seonaid, et al. “What do junior doctors want in start‐of‐term orientation?.” Medical journal of Australia 186.S7 (2007): S37-S39

- Spurgeon, Peter, Patti M. Mazelan, and Fred Barwell. “Medical engagement: a crucial underpinning to organizational performance.” Health Services Management Research 24.3 (2011): 114-120

- Markwell, Alexandra L., and Zoe Wainer. “The health and wellbeing of junior doctors: insights from a national survey.” Medical Journal of Australia 191.8 (2009): 441-444.

0 Comments